Levy first met the "sad-faced" and seemingly "undernourished" Charlie in 1909 when he saw him perform with the Fred Karno troupe in London. They became friends and off and on for the next twenty years, during which time Chaplin rose from obscurity to international fame, they often met. "I am privileged to call him friend," Levy wrote, "I have kept aloof from him for I did not want him to number me among those pests who are ever ready to claim acquaintance with and remind a celebrity that they 'knew him when, etc. etc.'"

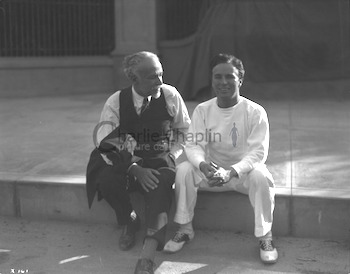

In 1929, Levy visited Chaplin at his studio during the production of City Lights. Shortly afterward he described the experience in an article for Hollywood Filmograph. Below is an excerpt:

Charlie's face shows very little trace of the early hardships--not to speak of the sorrow and strife of the later years of his chequered career. His boyish smile dissipates all that. When he exploited the baggy pants, antique derby and the nimble cane of his lean London days, nobody bothered him; but, in the days of his affluence unsuccessful imitators hung on to him like barnacles and complained that he (Chaplin) sought to restrict to his own use the rags that made him famous. The fools. It was not the colors he used that brought Rembrandt immortality, but how he used them.

There was a time when scandal sought to waylay and drag him down. Mudslingers were yapping at his heels like a lot of curs. Chaplin asked for no quarter and gave none. Subsequent events proved that he still holds his place in the affections of the people. The writer was present when Charlie, with the world seemingly against him, stepped upon the platform before a gathering of distinguished newspapermen at the New York Press Club. What a frantic demonstration in his favor there was on that day. It is the first time I have seen Chaplin holding back tears.

His philosophical outlook on life inspired, not by any particular "ism" or cult, but by his intimate knowledge of human nature, is the thing that makes Chaplin's companionship worth while. He steadfastly maintains that it is necessary for the artist to have known the pangs of hunger and to have experienced bitterness and hatred as well as love in order to bring out whatever of soul there is in him. Chaplin's way of jumping from one interesting subject to another is responsible for my doing the same thing in this article.

Limited space at my disposal prompts me to briefly chronicle the highlights in our studio chat. Chaplin has an incurable fear of crowds and a dislike of unnecessary publicity. "Charlie Chaplin belongs on the screen," he will say. "Any undue publicity regarding my petty aches and pains is distasteful to me and of no interest to the public...."

I asked Charlie his opinion of the talkies. "Entertainment without charm," he replied quickly, and then added, "while watching a silent picture each individual supplies the unspoken words according to his own understanding of the action. The dullard sees the story in his own way as does the intelligent, the wise, and so on--each one, as I said before, supplying his own understanding and everyone is pleased. But when the actor gives through the spoken word his own interpretation--then--well, there is bound to be disappointment. Yes, the talkie is undoubtedly entertainment, but in my opinion lacks charm."

I left Charlie grateful that I am privileged to call him friend--that is the sort of influence he has over those who know him best. Today the world is at his feet, but to me his is just the same lovable, lonely little clown I first met over twenty years ago.Click here to read the rest of the article.