↧

Brooding over the score for MONSIEUR VERDOUX

↧

German Ross Verlag postcard

↧

↧

Caricature by Alfred Frueh, 1931

↧

With Hedy Lamarr at a tennis match, c. 1941

↧

Photos by Homer Peyton, c. 1929

↧

↧

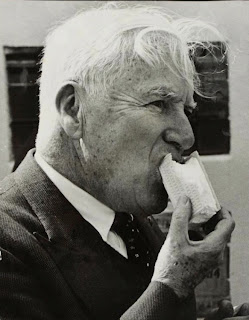

Charlie during a recording session for A King In New York, c. 1957

↧

Charlie & Food

- Charlie and I lived together, sharing the same room, for more than two years, and many's the time we cooked our dinners in our room. I fried the chops, while Charlie sat close to the door playing his mandolin to keep the landlady from hearing the sizzling of the meat over the gas--which was put there for lighting purposes only and not with any idea of cooking! --Stan Laurel, Film Weekly, Sept. 1929. Reprinted in Peter Haining's Charlie Chaplin: A Centennial Celebration.

- Perhaps his emotional state can be best illustrated by the food he eats. One week he solemnly informs us that he is a vegetarian, that meat is bad for one, and that lettuce and fruit form the ideal food. We all become vegetarian. The next week, he looks up and says: "What I need is a big juicy steak. Good meat to build up the body and brain." The following week it becomes cantaloupe filled with ice cream. "Everybody is eating too much," he says. "One can work much better on light lunches." His favorite dish I remember to be banana nut ice cream. --Virginia Cherrill, Picturegoer magazine, Dec. 9th, 1935.

- Every Tuesday at the Manoir was the cook's day off, and my mother used to take over the kitchen. She is surprisingly good over a cookstove. Tuesday was the day when she cooked for my father all his favorite dishes. None of the five star Cordon Bleu routine, but things he must have had, or wished he'd had, as a kid in South London...tripe and onions, steak and kidney pie, and stews with dumplings in them. But his craziest food fad is for a thing called Almond Joy. They're an American chocolate bar with an almond on top of them. The Swiss, with a swinging chocolate industry, don't encourage outsiders, and you can't buy Almond Joy there or in England. So any visitor he has coming in from the States loads up with candies for the old man. --Michael Chaplin, I Couldn't Smoke The Grass On My Father's Lawn, 1966.

- Most days we went to lunch at Musso and Frank's, a nearby restaurant that is to this day one of my favorites. Charlie, Henry Bergman (who appeared in any Chaplin films), Carter de Haven, Sr. (who had been a famous actor, and was the father of Gloria de Haven), and I would travel in splendor in Charlie's limousine. We always sat in the same corner table in the back room and had the same rather bored waiter. Almost anyone else would have been elated at the prospect of serving an artist of such eminence, but this one was onto all of Charlie's tricks and affected to be unaffected by them. But I loved every minute of it. Charlie had certain little songs with which he would order lunch, and we learned to sing them along with him. One of them, to the tune of "I Want A Lassie," went: "I want a curry; a ricy, spicy curry, With a dish of chutney on the side!" Another, to the melody of "Irish Eyes Are Smiling," went: "An I-rish Stew, with veg-e-ta-bles...!" All were performed with gusto. Diners who were startled by the sudden outbursts from the corner table seemed to be quickly mollified at the thought of enlivening their dinner conversations with the accounts of the luncheon entertainment. --David Raksin, "Life With Charlie Chaplin," Quarterly Journal Of The Library Of Congress, 1983

- The Chaplins ate outdoors as often as possible, on a large terrace overlooking a long expanse of lawn, and the mountains in the distance. Wild strawberries with heavy cream provided an occasion for a kind of dramatic production by Chaplin. He would choose the best-looking ones and present them, one at a time, to Oona, to himself, to a guest, and to each of his children--in that order. At the close of one such production, he shared a confidence with me. "Every once in a while," he said, "the old lady and I get out the caviar and champagne. And we don't invite anybody else. We sit here gorging ourselves. Just the two of us." --Lillian Ross, Moments With Chaplin, 1980

- Charles Chaplin likes stewed tripe and hates whiskey. He does like good wines, and drinks cocktails when the occasion seems to require it. Before prohibition, he always had a well-stocked cellar, never drank much himself, and always was a perfect host alcoholically. Since prohibition came, the same is true. Besides stewed tripe, he likes lamb stew. Those are two of his three favorite dishes. He dislikes seasoning, never uses sauces or violent condiments and doesn't care for highly spiced dishes. The one exception is curry, the hotter the better. That's his third favorite dish. He is utterly inconsistent about eating. Sometimes he will go for twenty-four hours or longer without taking a morsel. Then he'll eat four or five meals within the next day. He goes on diets but never keeps them up. He went rabidly on a raw vegetable diet for several days. "Look at animals," he said, "they eat raw vegetables and are healthy. The elephant is the biggest and strongest animal; he eats only vegetables." That night, Charlie ate two beefsteaks, rare.

His cook will work for a day or two to prepare an epicurean meal for him. Charlie sits down and it is served. He doesn't like the looks or aroma of something before him. So he leaves the table and goes to a cheap lunch counter and eats ham and eggs. He likes to eat at drug store lunch counters. His favorite restaurant is Henry's. The proprietor is his assistant director. When he is served something he likes very much, he takes as many as five helpings. It makes him violently ill. --Harry Lang, "No Talkies For Charlie," Photoplay, May 1930

- I went to Chaplin’s house. And they served dinner in the living room, and I remember they served chicken, loose chicken. And there was a bowl in the middle so you could help yourself. And the plate was quite large, and it was like a soup, but not quite—it was wonderful looking. And Charlie gets a spoon, slurp, both hands, the bread, slurp, and I’m going, "Oh my God! Uuuh!" And I’m going, "I don’t believe this!" ‘cause I’m very proper, and Oona was so proper, but you know, I figured she knows what to do, I’ll just follow what she does, just consider everything normal and keep on going. And it was the funniest thing, because it was such a shock! I’d never seen anybody schlurp it in and chew with an open mouth and with everything going at once. And laughing and talking and everything, and I’m going, "Oh my God!" --Interview with Marilyn Nash, Limelight magazine, Spring 1997

- Looking across to the little boats bobbing gently by the quayside at Avalon, I was startled by a deferential cough and turned to see Chaplin standing over me. He had come up from below as lightly as a grasshopper and was standing there in an attitude of a butler awaiting orders, head cocked expectantly, a napkin over the left forearm, his hand poised in a kindly step-this-way freeze. It was the silent movie call to breakfast and we went below. I have seen only one other man dispatch a meal with such speed. But whereas Adlai Stevenson, belying his general reputation for delicacy shovelled the stuff in with hands as pudgy as baseball mitts, Chaplin disposed of eggs and bacon and a wad of pancakes almost as a display of sleight of hand. One of the permanent pleasures of being with him was to watch the grace and deftness with which he performed all physical movements, from pouring syrup to swerving like a matador just out of the line of an oncoming truck. --Alistaire Cooke, Six Men, 1995

- At 6:00 p.m. the butler entered the salon to ask what I would like to drink and I was shortly joined afterward by Mrs. Chaplin. We both sat by the roaring fire enjoying our aperitifs when it occurred to me that Mr. Chaplin was late in joining us for his predinner gin and tonic. I asked Oona if she knew what had happened to delay him. She grinned and said, "Take a look out of the window." I got up and was quite unprepared for the sight that met my eyes. There, on a spot close to the staff quarters, stood a large portable barbecue they had brought from their home in California. Mr. Chaplin was garbed in a very heavy Crombie overcoat with its collar turned up to meet the rim of the black Homburg that had been pulled down well over his ears. He was gently turning the steaks and large jacket potatoes in between bouts of foot stamping and hand slapping, which, because of the extreme cold of this November evening, was so necessary in spite of the heat from the barbecue fire.

I felt deeply concerned that he should be exposed to such conditions and asked Mrs. Chaplin if I could go and help him. Mrs. Chaplin immediately replied, "No, Eric, don't go outside. Just leave him alone. This is his way of saying he's sorry for being such a pig to you today." I was deeply touched and felt that however difficult or unreasonable he would undoubtedly be in the future, this indication of a real and sensitive human being lurking within would help me to weather the storms and accept that this was part of the job. I might add that the meal was excellent. I have never had a better one and when at the end of it I was told that all the family would find it agreeable if from thence on I referred to them by their first names, I felt that I had really arrived. It had been a bittersweet day but it was the beginning of our long and mainly happy association.--Eric James, Making Music With Charlie Chaplin, 2000

- He was a great entertainer. It was always nice to go out with him. He'd do these amazing things with fish in the restaurant too. He'd always ask for a trout that's boiled alive. It's sort of twisted into a funny position and he would take the trout and look at it and say, "Oh, Emma, darling!" And kiss the trout on the lips, and suck out its eyes. We'd all be screaming. "Oh, daddy! Oh, how can you! It's so horrible." He'd ask for the wine, taste it, spit it out and the say, "Wonderful." He loved an audience and we, his kids, were a fantastic audience for him. --Geraldine Chaplin, Variety, April 2003.

- Chaplin conveys the stigma he felt, as a "nondescript of the slums" and underlines the depth of their destitution, by citing simply the absence of a home-cooked dinner on Sunday. "Even the poorest of children sat down to a roast that night," he reports, a ritual that distinguished one poor class from the beggar-class, "and we were that...The shame of it —especially on Sunday!" But they just couldn't afford it. On the other side of the same coin, something they could afford that Chaplin loved, was bread and dripping. This was fried bread sopped in beef juice: that was what impoverished English families ate when they couldn't buy anything else to eat. It was what was left from other foods: bread was used to sop up juice and melted fat from some meat that had been cooked and eaten, often long before. It was a staple of the poor. The night they returned from his father's funeral, this was all there was to eat--they even had to sell a little oil stove in order to buy bread. His association with it is pleasant: "There were times when I would stay home, and Mother would make tea and fry bread in beef dripping, which I relished...."

His wealth is not just protection, it is his revenge for the stinging humiliations he endured as a nobody. But his greatness? He continually returned to the term, "clown," "nothing but a clown," until I asked him directly whether he had any idea of what it was that linked him to the millions of people who felt so close to him, who loved his "tramp" who worshipped him as something more than an actor, as something more personal than a showman. His whole answer, in strong, decisive terms, was: "Yes. Bread and dripping." --Peter Steffens, "Charlie Chaplin: The Victorian Tramp," Ramparts, March 1965

↧

Charlie participates in a baseball game for charity, 1917

From Photoplay, June 1917:

A ball game rivaling in interest only that historic battle which destroyed the mighty Casey took place in Los Angeles' Washington Park on Saturday afternoon, March 31. The screen Tragics were up against the screen Comics. The Comics' lineup was as follows: Charles Chaplin, p.; Eric Campbell, c.; Charles Murray, 1b; Slim Summerville, 2b; Bobby Dunn, ss; Hank Mann, 3b; Lonesome Luke, If; Ben Turpin, rf; Chester Conklin, cf. In the same order of position, the Tragics were: Wallace Reid, William Desmond, George Walsh, 'Gene Pallette, Antonio Moreno, Franklyn Farnum, Jack Pickford, George Beban and Hobart Bosworth. Umpire and referee: Barney Oldfield and James J. Jeffries. The carnage was terrible. In the blood, dust and grand confusion the game broke up after two innings, and the Lord knows who won. The one really dreadful holocaust was the fanning of Wallie Reid — just as at least a thousand chickens had risen in the bleachers to give him the Chautauqua salute. George Walsh, a former pro, slammed the ball clear out of sight for a real home run. Chaplin pushed the sphere into the bleachers, and beat it straight across the diamond to second and back. Barney Oldfield properly called it a foul, whereat Barney was rolled in the dirt by fifty Keystone cops; after which, rising, he admitted that, owing to a superiority of numbers, he was forced to change his decision.Later that year, Douglas Fairbanks put together a team of movie stars for a baseball game against a man named Billy Sunday & his staff (Sunday was a former baseball player turned evangelist.) The game was a benefit to raise money for American soldiers. Charlie and Mary Pickford were named "honorary umpires." The movie stars won 1-0.

↧

THE PILGRIM (1923)

↧

↧

Syd Chaplin in Photoplay, 1926

↧

Happy 4th Of July to fans in the U.S.

This video shows Charlie lighting fireworks off the balcony of Marion Davies’ beach home in Santa Monica, CA, July 4th, 1928. Also in the clip are William Randolph Hearst & Harold Lloyd who can be seen walking towards the camera at the end of the video. The music is Charlie’s own composition, “Sing A Song."

↧

Charlie clowning on the boat to Hawaii, 1917

↧

With Douglas, c.1918

↧

↧

On the lawn of the Manoir, 1966

↧

Charlie visits Alla Nazimova on the set of her film, THE BRAT, 1919

↧

Photo by Hartsook, c. 1914

↧

With Paulette in Kyoto, Japan, 1936

↧

↧

Photo of Chaplin by the M. Lambert Studio in Nice, 1931

I believe the following photo (from the Maurice Bessy book), was taken at the same sitting:

↧

Charlie with Jean Cocteau, Le Soir Illustre, July 1958

↧

LAUGHING GAS, released July 9th, 1914

;

Charlie portrays a dental assistant who winds up impersonating his boss, Dr. Pain. This film may have been inspired by a Fred Karno sketch called, "The Dentist." Although Chaplin did not appear in the sketch, he was likely familiar with it. Chaplin himself hated going to the dentist & toothaches frightened him. He revisits dental humor again forty-three years later in A King In New York.

screenshots from Chaplin At Keystone (Flicker Alley)

↧